LAPAROSCOPY & DYE INSUFFLATION

Laparoscopy is generally regarded as being the gold standard for the assessment of pelvic health and for checking the patency of the fallopian tubes. This is part of the routine assessment of infertility. It is readily available both through the NHS and private sector

Tubal damage is the cause of infertility in about 15% of infertile couples.

The medical history and the findings on examination may strongly suggest a problem with the tubes:

- a history of pelvic infection/s

- major pelvic surgery causing adhesions post operatively

- termination of pregnancy followed by an inability to become pregnant with partners of proven fertility

- the finding of pelvic tenderness on examination

If there is nothing to suggest a tubal problem, it may be reasonable, at least initially, to give your tubes the benefit of the doubt. If however all the other fertility screening tests on you and your partner turn out to be normal there is still going to be a question mark hanging over the health of your pelvis. A tubal patency test must now be performed.

Some fertility treatments such as donor insemination and intrauterine insemination may involve you or the NHS in significant expense. It would be foolish to go through a series of treatments only to subsequently find out that a pregnancy could not have occurred anyway because of blocked tubes. You may find that your clinic will want a tubal patency test to be performed before agreeing to carry out these treatments.

It is possible to have severely blocked tubes without any known history of pelvic inflammatory disease.

How is laparoscopy performed?

Laparoscopy requires admission to hospital and usually a general anaesthetic. You are admitted to hospital starved having had nothing to eat and drink for the previous six hours.

A 1cm incision is made within or just below the lower edge of the umbilicus. Through this incision the abdominal cavity is inflated with carbon dioxide gas. This creates a large gas-filled space, which allows for much easier viewing of the pelvic organs.

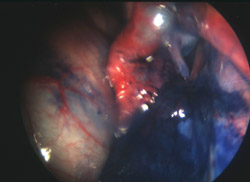

A slim-line telescope called a laparoscope is then introduced into the abdominal cavity and the uterus, tubes, ovaries and neighbouring organs are thoroughly inspected.

In the normal pelvis, the uterus, tubes and ovaries are gleaming with health. Neither the tubes nor the ovaries should be stuck down by adhesions. The presence of any abnormality such as endometriosis, fibroids or adhesions is noted.

To assess tubal patency, a blue dye (methylene blue) is injected into the cavity of the uterus via a special plastic or metal cannula placed in the canal of the cervix. The cannula also allows the surgeon to move the uterus in any direction. Sometimes an additional probe is inserted to move the bowel if it is preventing a clear view or to lift the tubes and ovaries and so facilitate the inspection of the pelvis. If the tubes are patent they first become slightly distended as they fill with the dye. The dye then spills out through the open ends of the tubes into the abdominal cavity.

If the dye does not enter either tube where it joins the uterus on each side, this could indicate an obstruction. The canal of the tubes is so narrow at this site that it is only just visible to the eye and may have become permanently blocked by previous inflammation and infection or temporarily blocked by muscle spasm. Sometimes the dye only passes through one tube and fails to fill the other tube at all. If the tube is obstructed at its outer end, as the dye is injected the tube becomes grossly distended (known as a hydrosalpinx). With increasing pressure the dye can be occasionally forced through the sealed off end of the tube but this nearly always closes itself off to become obstructed again.

In addition to assessing tubal patency, fine adhesions can be divided using delicate cauterising scissors. Mild endometriosis affecting the ovaries and the lining peritoneum of the pelvis can be destroyed using a form of cautery known as diathermy.

At the end of the operation the carbon dioxide gas is released from the abdomen and one or two fine stitches are used to close the incision.

When you are awake and alert you are told the results of the operation. The majority of patients are able to return home on the day of surgery. If you have significant discomfort you may be asked to stay in hospital overnight. It is advisable to have the next day off from work and rest at home.

Hysterosalpingogram versus laparoscopy

A hysterosalpingogram (HSG) X-ray (see Hysterosalpingography information) for tubal patency will give approximately 75% of the information obtained at laparoscopy. This is because even a normal X-ray cannot exclude the presence of adhesions that may be enveloping the ovaries and prevent the eggs from having access to the open ends of the tubes at ovulation.

HSG and laparoscopy and dye testing complement each other as they assess tubal patency in different ways. The dye used in HSG shows the shape of the cavity of the uterus and the presence of any filling defects like small fibroids or polyps that may disrupt the normal smooth outlines of the cavity. Laparoscopy directly assesses the normality and health of the pelvis and can confirm or exclude the presence of adhesions. If at laparoscopy the pelvis is seen to be 100% healthy in appearance but no dye is seen to enter either tube, a subsequent HSG can be helpful in clarifying the cause. If the HSG shows a free flow of dye through both tubes, it can be safely assumed that tubal muscle spasm was responsible for the "failed" dye test at laparoscopy.

Are there any risks to laparoscopy?

One risk of all surgery is the risk of anaesthesia. However most of the risks of a general anaesthetic affect the very tiny (babies), the very sick and the very old. It is usual for the anaesthetist to see you before your operation and assess your suitability for surgery. The anaesthetist will also see you when you wake up after your operation to check that you are recovering normally.

A particular risk of laparoscopy is trauma caused by the insertion of the needle that introduces the carbon dioxide gas and by the larger instrument that is inserted to carry the laparoscope. Very occasionally these instruments can strike and damage underlying structures. These structures include bowel, bladder, uterus and, very rarely, even blood vessels. Curiously the risk is greatest for the very slim patient with very little fat in the abdominal wall. This does not mean that the surgeon has been incompetent. It is possible for bowel to be stuck to the inner wall of the abdomen at the umbilicus, at the very site that the instruments will be inserted. The laparoscopy will indicate any damage. This may require immediate surgery to correct.

March 2009